There is a stock I looked at a few years ago that has always stuck in my mind, and that is London based Premier Foods ($PFD.L). To me it is the perfect simple example of how even a great business can be destroyed by leverage. Before the crisis it was a company that had so much going for it, a producer of many reputable food brands in the UK with a moat worthy of giants like Pepsi. But in 2006 the management and board made a catastrophic decision. They engaged in the leveraged buyout of two competitors, which resulted in Premier becoming the largest food supplier in the UK. This was supposed to be a transformational point in the history of the company, and it certainly was….for all the wrong reasons. Premier is a story of what happens when a company has everything going for it, but is sunk by too much leverage and bad management.

Pre-acquisitions

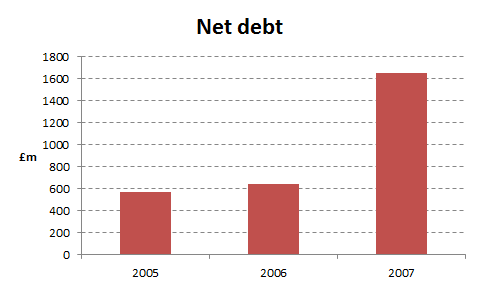

Premier has a straight foward business. It produces branded food products such as bread, jam, vinegar etc and sells these onto customers, which are usually large retailers such as supermarkets. In 2005 Premier was far from a conservatively run company. It had strong net profit margins of 10.6%, but net debt was £568m, almost 7x net profits. This high debt load also led it to have negative book value, which may be viewed as good for a business as it shows it has high returns on invested capital, but in this case also showed this was a very leveraged company. Despite these shortcomings it was a great business with strong organic growth. In order to fund the acquisitions however, Premier would need to take on more debt. A lot more.

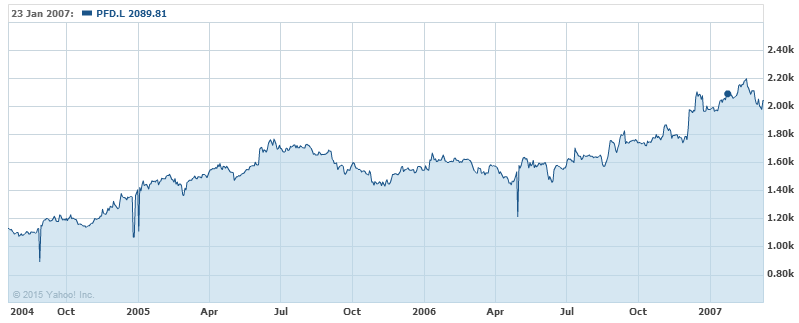

Despite this, it’s fair to say that the markets responded favorably to these leveraged buyouts.

The acquisitions

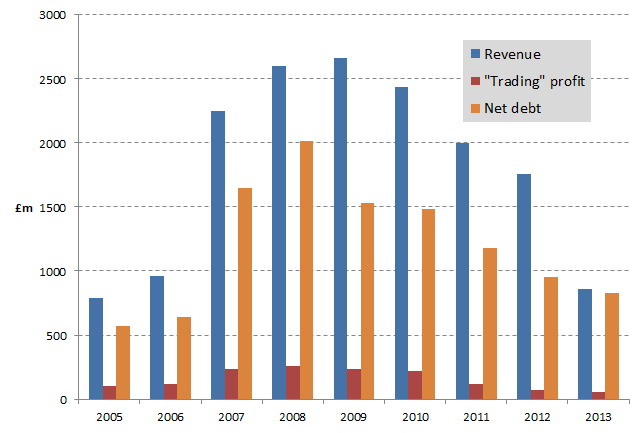

In 2007 when Premier had completed the acquisitions of two competitors, the UK economy had been doing well for a number of years and Premier’s organic growth had likewise been strong for years but the addition of the new businesses would completely transform the company. To understand the scale of the change these acquisitions represented, consider that Premier’s revenue rose from £680m in 2005 to £2,200m in 2007. Before the consolidation, management had the usual positive things to say about the benefits the newly combined group would bring, lots of talks of ‘synergies’ and cost savings.

“The acquisition will create a more efficient business and removing the overlap in manufacturing facilities and administrative functions will generate pre-tax savings of £28m. Significant progress in integrating the business has been made. We have already consolidated administrative functions and announced the closure of two sites at King’s Lynn and Ashford and significant investment in three other sites. Management systems integration is underway and remains on track for completion at the end of March 2007.” – Chairmans letter, 2006 Annual Report

But the optimism was short lived, for even before the financial crisis occurred, the integration ran into problems. Investors must have been sorely disappointed in 2007, when the company slashed its dividend, citing pressures on input costs, and increased capital expenditure being necessary. Despite this, it only had positive words to say on the acquisitions.

“We estimate that the synergy run rate across both Campbell’s and RHM had reached £47m at the end of 2007. We expect to complete the integration on schedule by the end of 2009.” – CEO letter, 2007 Annual Report

Except that the timeline had now shifted from 2007 to 2009 for completion of the integration. At the same time, the ‘exceptional costs’ where piling up and wouldn’t stop for years.

The Crisis

Premier should have been a great example of a company that could weather a crisis. It sold quality branded food products, non-discretionary consumer goods that are relatively insensitive to the general economy. Instead it was at the mercy of the debt markets, which finally woke up to the fact that it had no real hope of paying back its debts. Despite this, the chairman still did not admit fault.

“…the stock market became concerned over our debt position and related covenant and repayment terms, given the collapse in the credit markets. This debt position was largely created by the acquisition of RHM, our inability to sell non-core assets in the 2008 financial climate, and our higher working capital needs as a result of raw material inflation. The RHM acquisition however is, strategically and commercially, a success, and the realisation of synergies, an important achievement.” – Chairman’s letter 2008 Annual Report

In 2008 Premier’s losses caused its debt to balloon to over £2bn. As a consequence it went with its hands outstretched to the markets, issuing new equity to reduce debt and strengthen its balance sheet. Despite raising almost £400m, net debt was still a staggering £1.5bn.

Post Crisis

The company was now in a tough position. Its cash flow was only around £100m in optimistic scenarios, and its lenders were not content to wait over 15 years for Premier to pay back its debts. Premier would now need to sell off parts of its business to raise money to pay down debts.

In 2010 a new Chairman took over and this marked a small turning point for the company where it finally at least acknowledged its debt was a problem and that it needed reducing, however shareholders couldn’t be too enthusiastic given he seemed like another crony who preferred to gloss over problems. His defense of the previous chairman is quite shocking.

“As referred to above, I joined as Chairman with effect from 1 October 2010 succeeding David Kappler. On behalf of the Board, I would like to thank David for his significant contribution to the Group since its flotation in 2004.”

Who thanks someone for bankrupting a company and running it into the ground? But he didn’t last long, in 2012 the company had yet another chairman (and had been through another 2 CEOs). Unfortunately again for shareholders, the new chairman was from the same board that had overseen the virtual destruction of the group in 2007.

Over the next few years Premier began to sell off the assets it had bought only a few years earlier. As a result the company began shrinking in size quickly. This allowed them to pay down debt quickly, but at the same time profits reduced as well, so the business has remained highly leveraged.

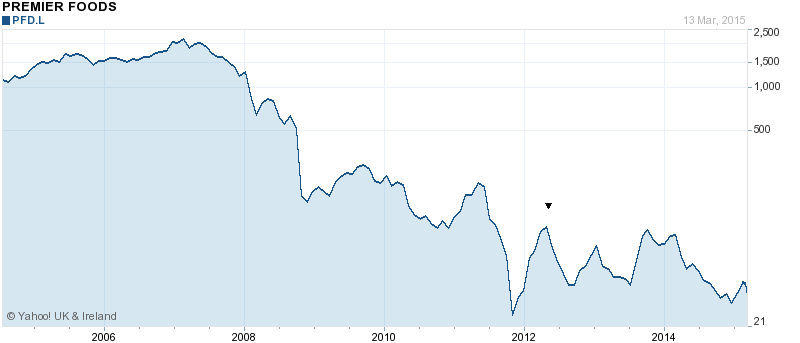

This has caused a spiral downwards, as profits are hit more and more by disposals the debt load is still overwhelming profits. And how have shareholders benefited from this shocking case of poor management?

What is still shocking is that this company’s market cap is still over £300m, with net debt still at 8x EBITDA. And I have not even mentioned its considerable pension deficit, which is yet another drain on its cash.

What is still shocking is that this company’s market cap is still over £300m, with net debt still at 8x EBITDA. And I have not even mentioned its considerable pension deficit, which is yet another drain on its cash.

Lessons Learnt

I think this is a perfect example of how even a wonderful business with a strong competitive moat can be destroyed by poor management and leverage. This case study is so simple yet demonstrates clearly why investors should avoid leveraged companies, and doesn’t require a lot of hindsight bias to see why it ended badly.

There is no doubt that such leveraged buyout situations can actually make investors rich very quickly. After all if the profits of the company had continued to grow and inflate then the debt load shrinks and equity rapidly increases. But don’t be fooled, this get rich quick scheme comes with considerable risk, as Premier shareholders have found to their peril.

The story is still not over for Premier Foods, it’s debt is still a burden, and it cannot weather another storm. It is trapped in a cycle of downsizing its business to reduce debt, who knows where it will end.

Leverage not only can result in catastrophic losses like in Premier’s case, but it also puts you as an equity holder at the back of the queue when a company generates cash. Net profits are worth nothing to a shareholder if they are going straight to the bank instead of to you as dividends or share buybacks. Excessive debt is a black hole that sucks cash from a business. You will find lots of these companies selling at low P/E ratios and so may consider them cheap but don’t be fooled.

Disclosure: Author has no position in PFD.L