The western world is finally ‘recovering’ from the greatest recession since the 1930s. Many parallels have been drawn with the 1929 crash over the last few years, including politicians citing ‘lessons learnt’ from how lawmakers reacted in the 1930s and why this time, it’s different. We are now 6 years since the bottom of the stock market crash in 2009, and an unprecedented amount of money has been added to the economy, with little overall impact on inflation. I usually don’t focus too much on the macro when it comes to investing, but I find a brief look back to 1937 tells an interesting tale and may give us a clue as to what the future holds.

Let’s go back to the 1930s, to a similar number of years after the stock market crash of 1929 and the following recession in the early 1930s. The USA was going strong, unemployment had fallen from 25% to 14%. Iconic construction projects such as the Hoover Dam and the Golden Gate Bridge were completed in 1936-37 and President Roosevelt was sworn in for a second term in a landslide victory. But things soon took a turn for the worse, and the Hindenburg disaster in New Jersey in 1937 was unfortunately a symbol of the economic disaster yet to come. If you take a look at the Dow Jones throughout the 20s and 30s, note what happened in 1937. That may look like a blip in comparison to the 1929 crash, but it was in fact a 50% decline in the stock market.

The US actually went back into recession in 1937-38, about 3 years after the bottom of the stock market crash. So what happened?

This time wasn’t different?

Contrary to popular opinion, the great depression was not followed by a period of tightened monetary policy and restrictive government. In fact when Roosevelt first took office in 1933, he immediately started to spend money on public construction projects (such as the aforementioned Golden Gate Bridge and the in progress Hoover Dam), all funded by an increase in government spending, fuelled by debt.

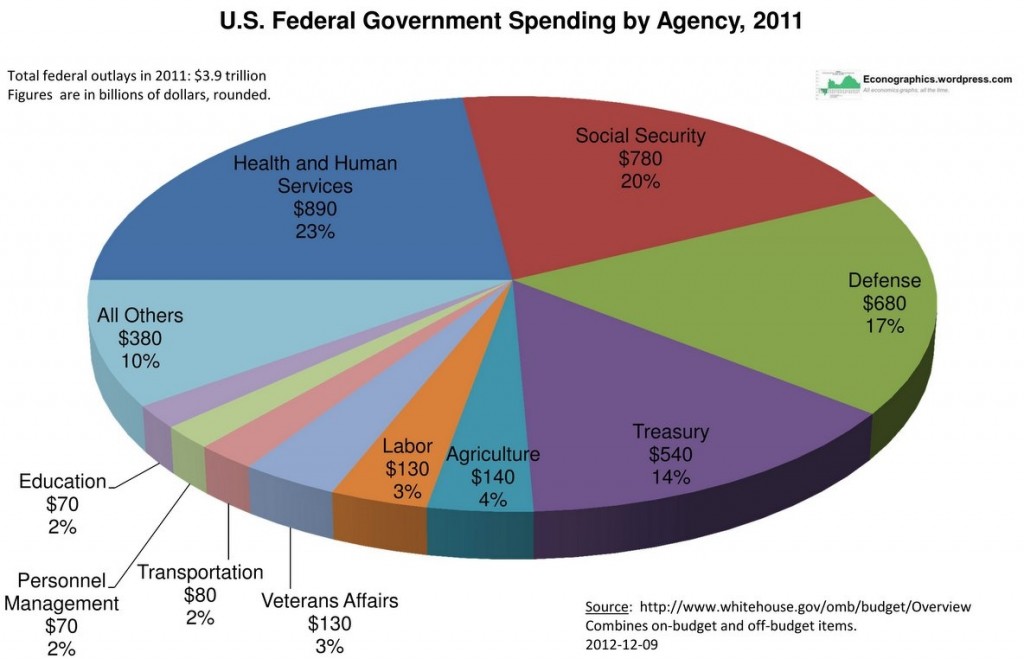

But perhaps the biggest impact was from the monetary expansion which also occurred during this time. The money supply increased by 42% between 1933 and 1937. This led to lower interest rates which fuelled credit and the economy. This all sounds oddly familiar doesn’t it? We have been told by politicians that we have learnt from the mistakes of the 1930s yet we are apparently following the same policies (not that I think these are right or wrong, just that they are the same). Except rather than spending money on construction and infrastructure, today the US spending is heavily driven by the costs of Medicare, Medicaid and Defense.

Source: Econographics

This time was different?

Roosevelt’s first term was a huge success, as proved by his second landslide victory in the 1936 election. The spending and expansionist monetary policy stimulated economic growth to such a degree that it meant the USA’s debt burden did not actually rise relative to GDP from 1933 onwards. In fact it didn’t rise until the advent of World War II.

This is in stark contrast to what we are seeing today, where total US debt is 74% of GDP and still rising. That could be due to the type of spending the deficit is funding. It is not funding construction and large projects but being swallowed up by the healthcare industry. We are also not seeing the large wage increases that accompanied the economic recovery of the early 1930s.

The 1937 recession

So fast-forward to 1937, and what happened? Roosevelt decided to try and balance the budget, and withdrew the life support that the US economy had been on. Firstly, loose monetary policy was tightened and the reserve requirements for banks set by the Fed was increased. Secondly the US deficit was slashed from $4.3bn in 1936 to $2.2bn in 1937. Current popular theory holds that these were the causes of the recession, which is why the current government is resisting calls to reign in spending, and why central banks are barely even considering raising interest rates.

But in economic circles there is still a lot of debate over what caused the 1937 recession. Some note that although the Fed’s reserve requirements were increased, lending did not actually start to decrease until after the stock market had begun to collapse, suggesting that banks were reacting to a more risk averse environment rather than regulatory requirements. Hence they conclude that monetary contraction was a symptom of the recession, not the cause.

Others point out that US government spending in 1935 was actually lower than in 1937, yet the US economy was growing rapidly at that time. They conclude that the cut in government spending could not have caused the recession.

There was also the fact that during the early 30s, with unrest in Europe, large amounts of gold had been flowing into the US, stoking monetary expansion and inflation. In 1934 the US re-pegged the dollar to gold and later the Treasury went further and decided to sterilise all gold inflows from December 1936. This meant its new gold holdings were held in an inactive account rather than with the Fed, so they didn’t add to the money supply. Hence the monetary expansion suddenly halted and the economy stalled. Proponents note that the economy only went on to recover when the gold sterilisation policy was abandoned.

I don’t claim to know which of these opinions is correct, but I think it tells an interesting tale of economic prosperity and a booming stock market suddenly taking a turn for the worse. So with current stock markets at all-time highs and economic data improving, we should not be complacent and extrapolate into the future without considering the risk of another 1937. Governments and central banks across the world seem to think they know the mistakes of the past and that they are pulling the right levers to prevent another downturn. All I know is that every single politician or banker that has claimed to have control over the cycle of boom and bust has turned out to be wrong. It’s always easy to look back at recessions with hindsight and apparently identify the culprit, but as we know it’s never stopped them happening again.

Good post. My gut tells me that all the current extreme monetary expansion is not going to have a happy ending, though when and how I’m none the wiser. With interest rates at record lows, I guess the U.S. could go back to the Gold standard, though I doubt there is any political appetite for that to occur (I have some sympathy for the AustrIan school of economics and also Jim Grant !). Personally, zero or low interest rates are a bad thing, as I get zip return on my cash yet am reluctant to stick everything into the stock market, especially with values being what they are. If I had to punt, it would be on inflation rising. Interesting times indeed !